Published by Courtauld Reviews, Issue 4, March 2010

Tate Britain, London

24 February - 08 August 2010

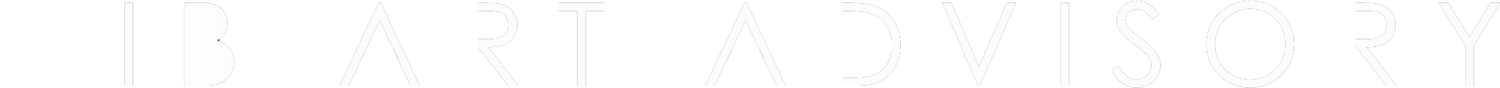

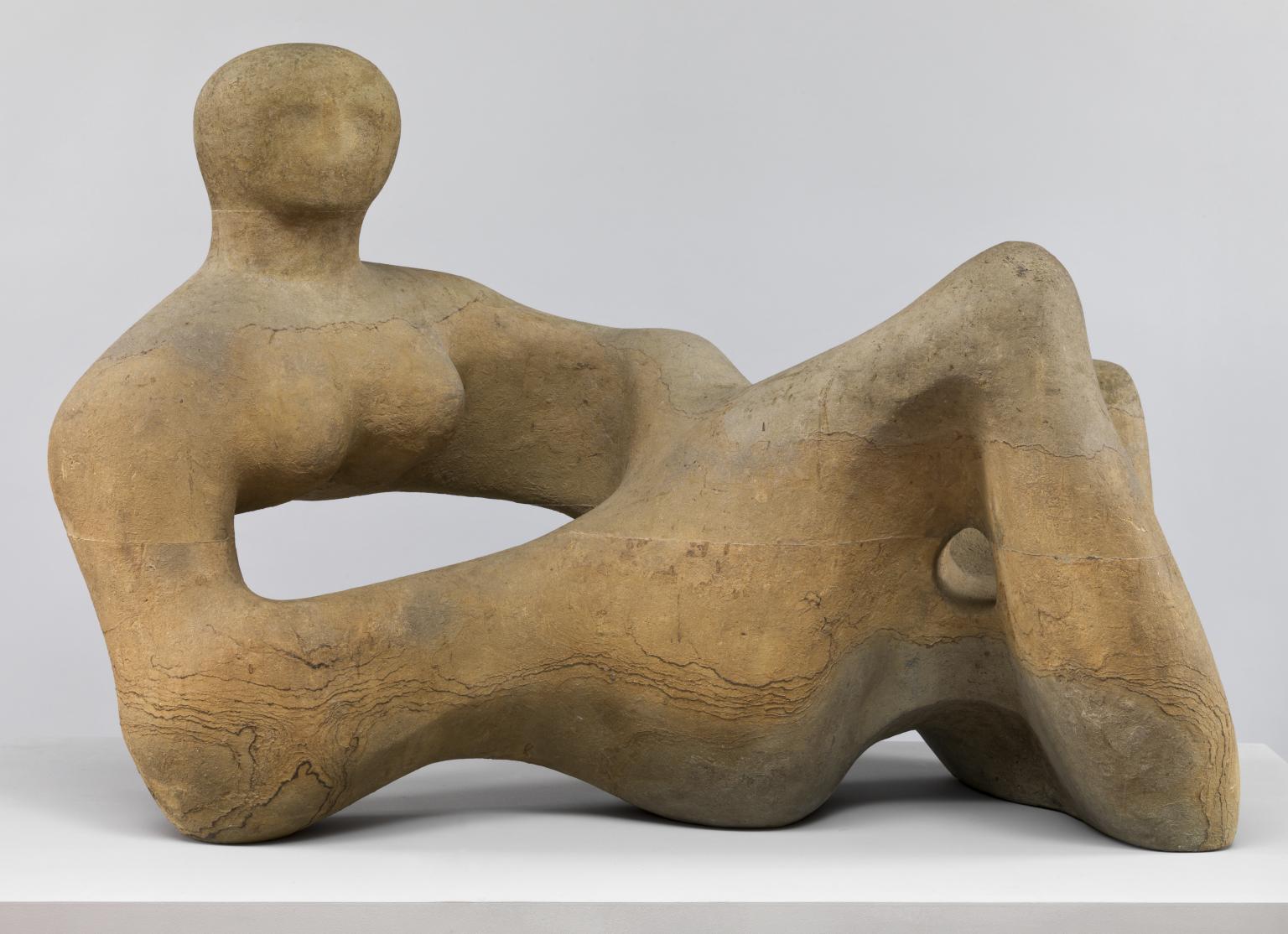

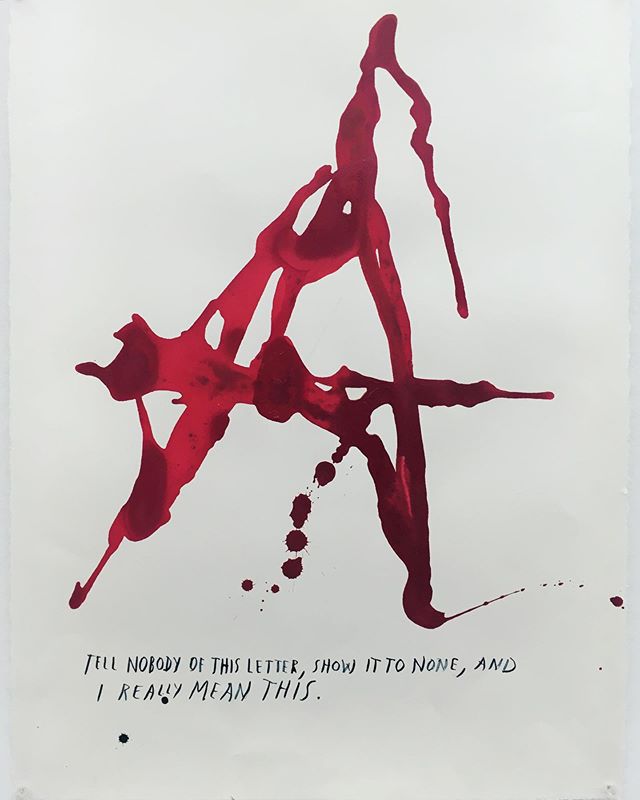

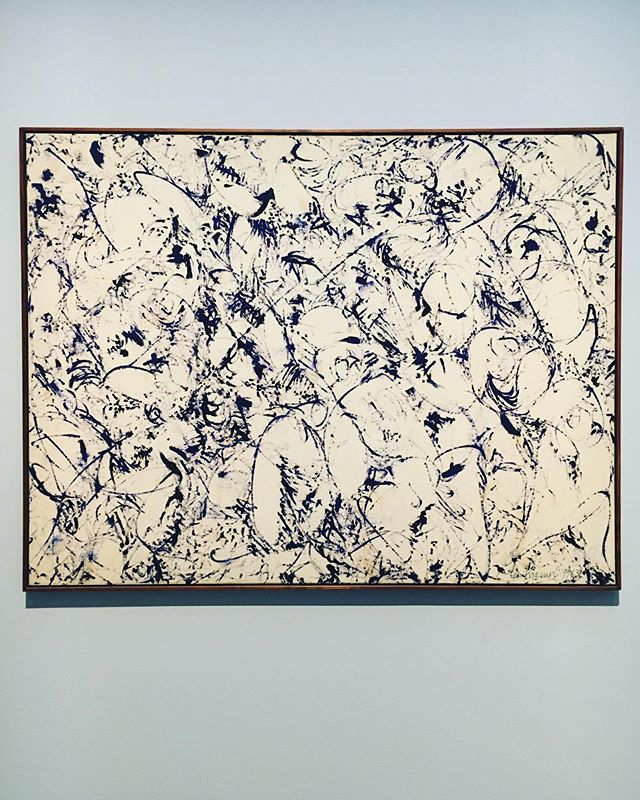

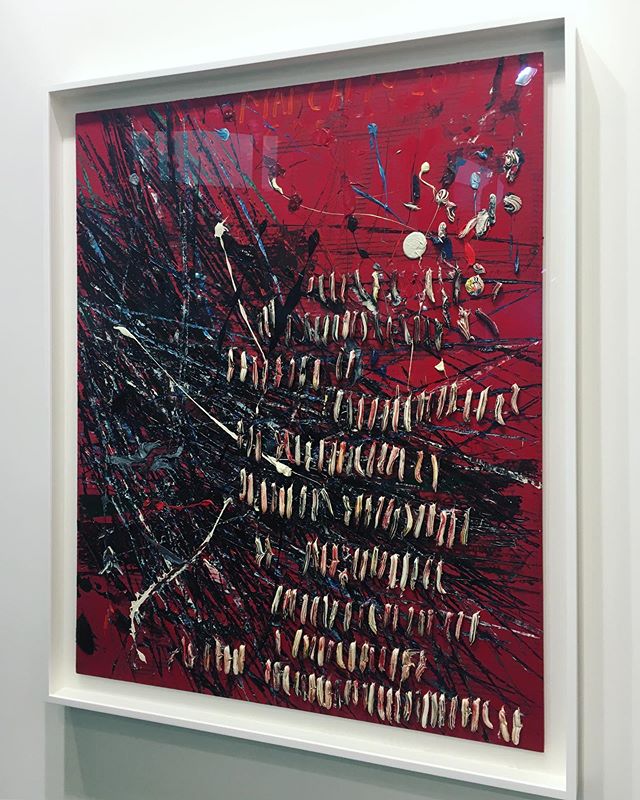

While the 1988 Henry Moore show at the Royal Academy presented the sculptor as a romantic, Tate Britain attempts to reinvent Moore (1898–1986) as a radical, experimental and avant-garde artist. The artworks are given center stage in this exhibition, uncovering a dark and erotically charged dimension to Moore’s work that incites visitors to revisit their preconceived notions of one of Britain’s best-loved sculptors. Through the presentation of over 150 stone sculptures, wood carvings, bronzes and drawings by the artist, the exhibition explores the trauma of war, the advent of psychoanalysis, and new ideas of sexuality, non-western art and surrealism as frameworks within which Moore can be reborn.

While the show’s revisionist aims are clearly stated in the introductory panel and constantly reiterated throughout the exhibition by means of wall texts and quotes, it is questionable whether these aims are successfully communicated to the viewer. The gallery spaces are decidedly empty of information. The wall panels are sparse and the object labels only provide tombstone information. Similarly, the room divisions seem disparate and the display of works, random. While some rooms explore Moore’s cultural influences (Room 1: World Cultures), others focus on subject matter (Room 2: Mother and Child), isms (Room 3: Modernism), historical periods (Room 4: Wartime and Room 5: Post-War) and materials (Room 6: Elm). For some visitors, this lack of direction may privilege a sensory response to the artworks or encourage viewers to address their own subjectivity. For others, the schizophrenic structure of the exhibition may elicit mystification and misunderstanding. While the exhibition engages with the canonical narrative of modernism and gestures towards meaning, there is no coherent grand narrative, as it is riddled with inconsistency. Hence, the show can be described as distinctly postmodern, but is this postmodern construction intentional?

The answer is not immediately clear, as today’s art museum is a postmodern construction in itself. The curator is no longer the sole voice in an exhibition, since different departments often have divergent agendas. This has created a decentered museum and is reflected in the microcosm of the narrative of the Henry Moore exhibition, which also possesses a plurality of voices. Thus, perhaps the more interesting question is: Have the curators made a conscious intellectual choice to present the material in a postmodern way, or is the exhibition an indirect result of the postmodern construct of society in late-capitalism which also formulates the structure of the museum? The most plausible answer appears to be simply both. While the exhibition presents a revision of modernism, the decentered museum structure shapes and emphasizes the postmodern convolution of the narrative.

Arguably, the audio-guide provides the strongest reading of the exhibition, as it successfully pulls together these different voices. Without it, the various modes of interpretation do not interrelate. In many ways, this digital technology becomes a lifebuoy to navigate the exhibition, as it constructs threads of meaning throughout a gallery space which often lacks cogency. Moore’s Reclining Figures and Mother and Child themes, for example, are interspersed in the various rooms, creating a sense of continuity. Similarly, the audio commentary constantly refers back to Moore’s approach to materiality, as well as elements from the artist’s biography, to construct the meaning of the various works included. It can be argued that these different ribbons running through the exhibition by means of the audio-guide give the exhibition its “true” meaning, negating to a certain extent its postmodern structure.

While it is difficult to assess if the curatorial aim of the exhibition has been attained, it is immediately clear as one walks through the gallery space that there is ‘Moore’ to the artist than meets the eye. Arguably, this is where the success of Tate’s Henry Moore exhibition lies.