Published in Hermie Island, 28 October 2013

Regent’s Park, London

18 - 20 October 2013

Daisy lies on the temporary gallery floor seemingly unaware of her surroundings. Her right wrist wears a label bearing her name – a name that conjures ingenuousness and youth in its purest form. Her body is contorted; her actions, suspended in animation. Transfixed, visitors gather. Disheveled lackluster hair is juxtaposed against a vivid pink dress and fluorescent yellow leotards. Her face conveys a tragic look learnt, as her eyes wear an expression similar to those favored by Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Marc Caro in La Cité des enfants perdus (The City of Lost Children, 1995). Her angst is palpable. An archetype of childhood and innocence lost, she communicates the bitter existential emptiness of contemporary life, and forces us to examine our own materiality within the art space. Unprompted by the gallery staff, Daisy stands. Visitors look on, eagerly awaiting the conclusion of her performance. She runs to a woman with a pushchair as a gallerist impatiently snatches the label – the conduit for this social experience – from her and places it next to its respective art piece. Stripped of her contextual framework, ‘Daisy’s’ actions are rendered meaningless. Inadvertently engaging with Nicolas Bourriaud’s esthétique relationnelle or relational aesthetics, ‘Daisy’: The Rise and Fall (more accurately renamed) literally boasts the prevailing “anything is art” cliché summary of contemporary art. Mother and child disappear behind a row of glistening Jeff Koons sculptures at Gagosian, as a wave of nervous laughter erupts within the space and red Louboutin soles scatter. This is Frieze 2013. Welcome to the arts club.

This year marks the eleventh incarnation of Frieze Art Fair, and with it comes a new wave of international collectors, dealers, curators, critics and visitors who mistake children for artworks. 151 galleries unite to create a dizzying FoMO fairground where tortoise framed glasses, slicked back power hair, statement jewelry and Chanel handbags (“Chanel Bags the Biggest Fans at the London Frieze,” the Guardian reports) parade along the aisles to see and be seen. Constellations of star-studded bomber jackets and Cuban heels form around works that encourage viewer participation – a tangible side effect of our current obsession with surface-level interactivity, no doubt. Find it in the Twitter feeds, Facebook likes and incessant hashtagging. This is what our generation craves.

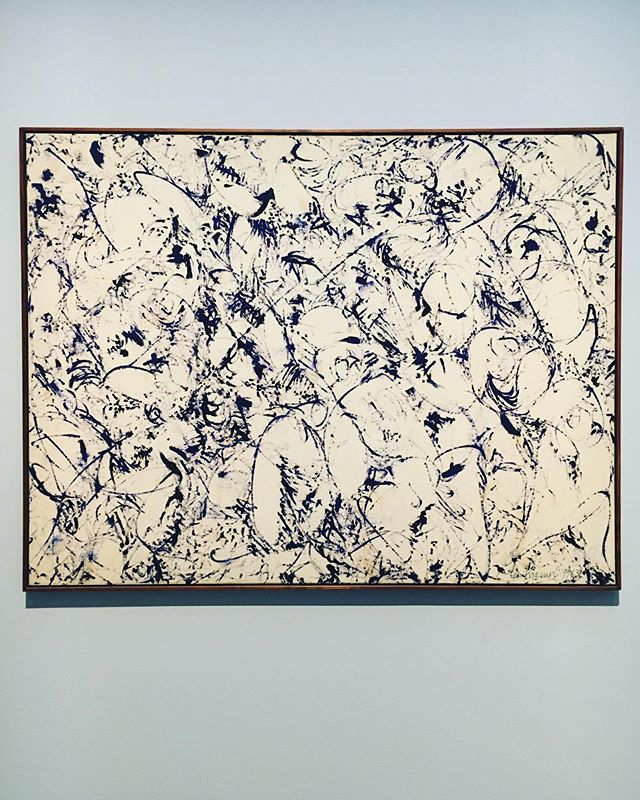

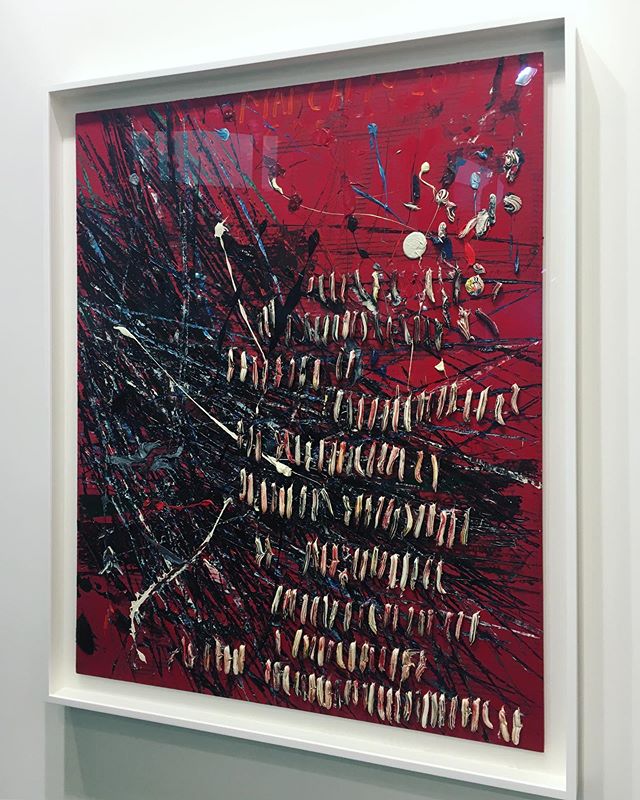

Frieze Projects, a program of artist’s commissions realized annually, amplifies this circus funfair vibe, exhibiting experimental audience-participatory artworks. Ken Okiishi’s carnival-style installation is no exception, as visitors are invited to fire paint guns with the help of remote controlled robots. The colors red and green explode on random targets, whilst they are violently bombed behind a protective Perspex sheet. Next door, Lili Reynaud-Dewar transforms an intimate bedroom setting into a public arena (Untitled, 2011). Comfortably nestled on the bed’s plumped-up pillows, the performance artist reads Guillaume Dustan’s autobiography Dans ma chambre (In My Room, 1996) as an ink fountain freely flows out of the mattress’ center, saturating everything in its proximity. Acting as a sounding board, the spectator becomes an integral part of the work.

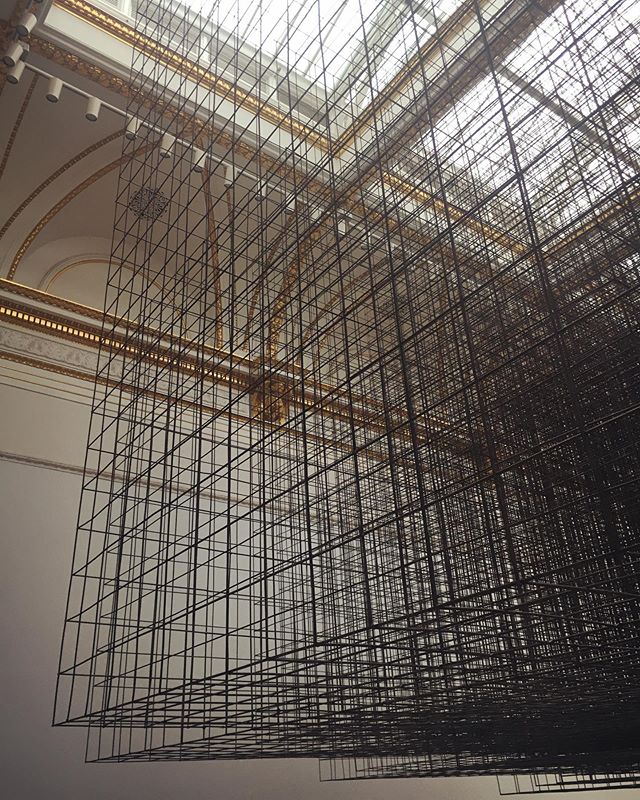

Emerging from Frieze Projects, an unruly queue begins to form at the Stephen Friedman Gallery to enter Jennifer Rubell’s Portrait of the Artist (2013), a white fiberglass sculpture of a colossal pregnant woman lounging on her side. In place of her belly, there is a void within which viewers can climb and morph into living fetuses for the ultimate rebirthing experience. A few rows down at PSM in Frame, one is invited to face impending doom by standing beneath Eduardo Basualdo’s mammoth beehive-like formation (Teoria (Theory), 2013). Vacillating between the repressive and liberating strains of calamity, its cataclysmic quality incites the beholder to fathom the installation’s eerie impenetrable depths. From protected womb to looming mortality, the visitor’s journey echoes John Barth’s mythotherapeutic notion that everyone is the hero of his own life story.

A star in her own cinema, a woman stands before Olafur Eliasson’s Fade Door Up (Working Title) (2013, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery), her camera phone at the ready (#selfie). The mirrored piece reflects her body while concealing her face. Spectator and artwork amalgamate to become one. At first glance we dismiss it as a vacuous encounter, yet it speaks of popular culture, circularity and feedback. Further along, a spiraled Plexiglas pavilion by Dan Graham (Groovy Spiral, 2013, Lisson Gallery) warps the booth it occupies, enticing visitors to enter. Cocooned in the spherical structure, participants escape the surrounding cacophony. On display to onlookers, bodies navigating the glass maze articulate the social implications of architectural systems. Restructuring our perception of time and space, the installation demands a reflection of our selves within the art gallery. More importantly, it encourages viewer participation, engagement, interactivity and play – something too easily forgotten at a fair where pretension and posing often prevail. Much like ‘Daisy’, it is through these humble encounters with the artwork that meaning is construed.