Published in MTArt, 19 June 2017

Marine excitedly guided me through the deserted streets of Kreuzberg in search of The Feuerle Collection. Hidden from street view, the collection is housed in a German Second World War telecommunications bunker renovated by British architect John Pawson. Eschewing the white cube space in favor of concrete walls and dim spotlights, visitors are plunged into a world of collector Désiré Feuerle’s making.

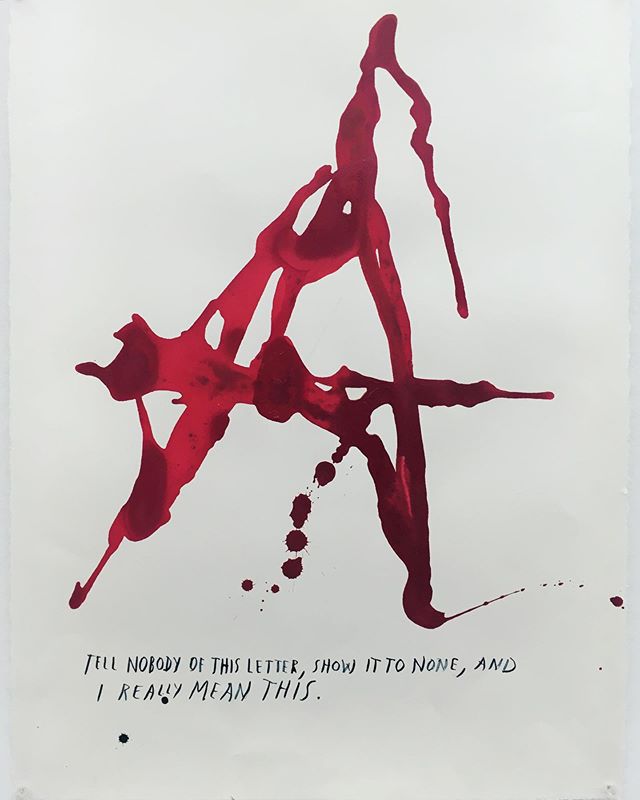

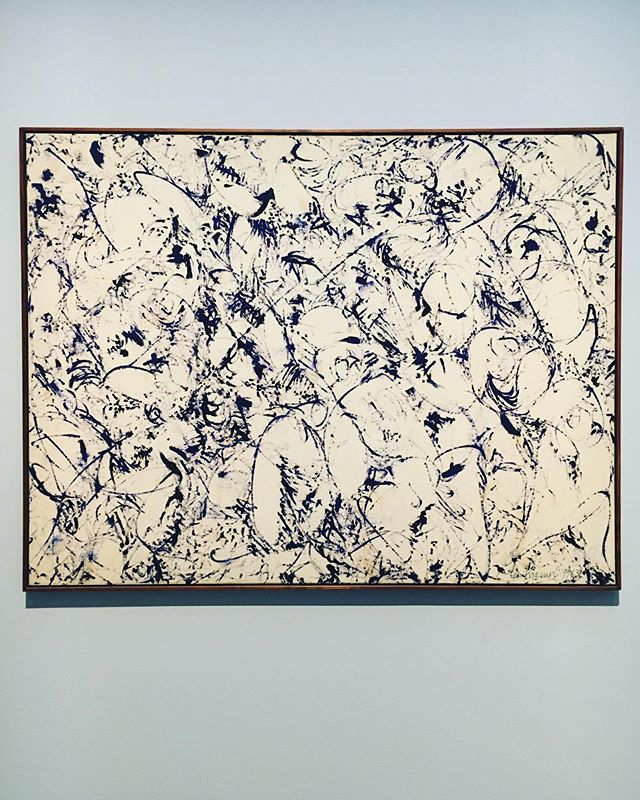

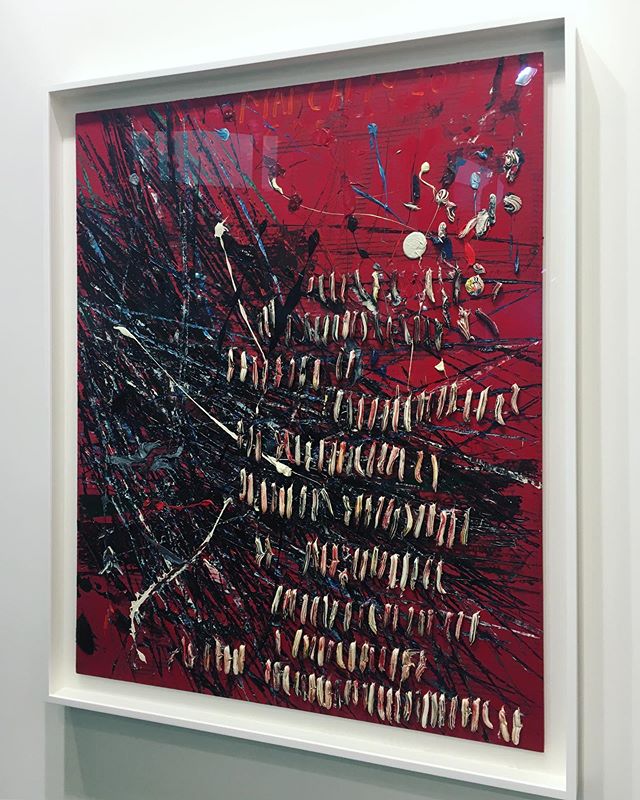

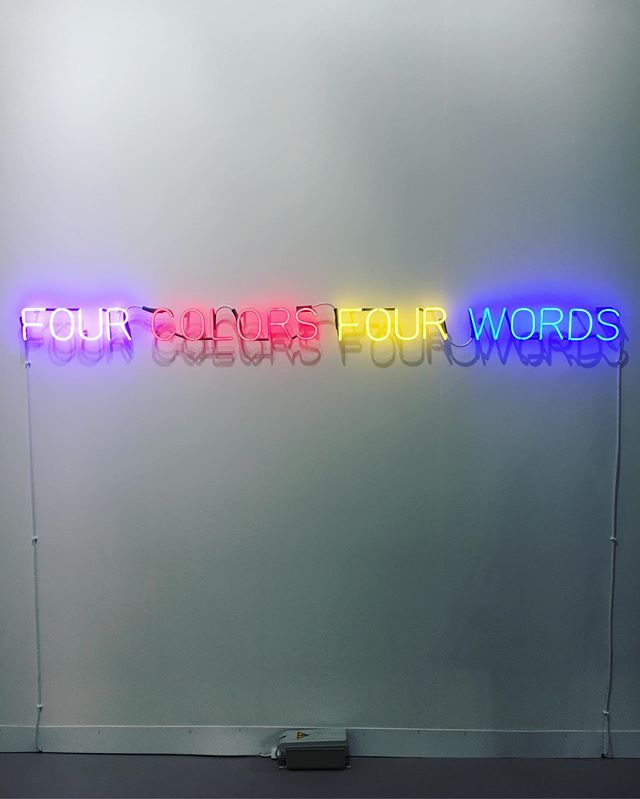

Juxtaposing international contemporary artists with Imperial Chinese furniture and ancient Southeast Asian art, the museum’s considered curation initiates a dialogue between different periods and cultures. Presenting visitors with a reinterpretation of ancient art, the pieces can be perceived through an alternative lens. Hence, artworks by Anish Kapoor, Cristina Iglesias, Zeng Fanzhi, Nobuyoshi Araki, James Lee Byars and Adam Fuss rub shoulders with Khmer sculptures from the 7th – 13th century and Chinese pieces from the Han and Qing Dynasties (200 BC to the 18th century).

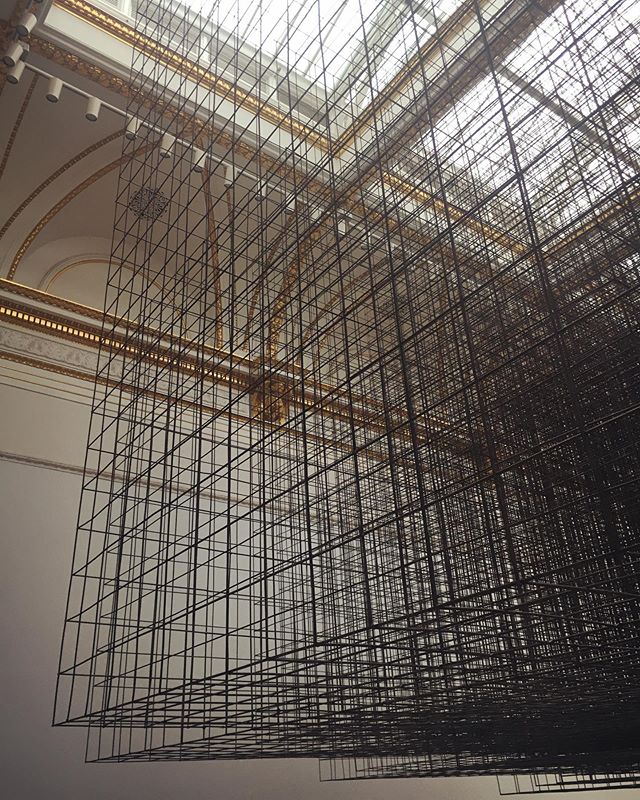

The colossal museum space – measuring 6480 m2 to be exact – is composed of two main exhibition rooms on the ground floor and the lower ground floor, housing a Sound Room, a Lake Room (reminiscent of Richard Wilson’s “oil room” art installation 20:50) and an Incense Room. Arguably, it is the setting that lends the space its divine quality. In Pawson’s own words:

“It is difficult to think of places more charged with atmosphere than these monumental concrete structures. They fall very much into the category of ‘engineers’ architecture that so appealed to Donald Judd. I knew from the beginning when I visited the site and first had that visceral experience of mass that I wanted to use as light a hand as possible. Concentrating all the effort on making pristine surfaces would never have felt appropriate here. Instead this has been a slow, considered process – a series of subtle refinements and interventions that intensify the quality of the space, so that all the attention focuses on the art.”

We are encouraged to “let the music pierce our hearts” before being led to the pitch-dark preamble Sound Room where John Cage booms out of the speakers. As we enter the exhibition space (the distant echo of Cage still with us), our irises expand to allow the little light in. Having worked with private collections for nearly a decade now, never have I seen a display quite like this one; each artwork – spotlighted with a single light – appears to be cocooned within its ethereal aura. Here, the sensory experience is privileged as the artworks take center stage.

It is precisely through this unique approach to curating that the artwork is elevated to new levels of contemplation. To redouble and rephrase, it is the oeuvre’s greater contextual framework that triggers within the beholder a genuine sense of awe.

I cannot help but draw parallels with religious iconography and pious modes of display. While the Catholic Church’s uncanny ability to violently overwhelm may raise the eyebrow of a non-believer, it is irrefutably amongst the strongest impulses for the creation of art in Europe since the inception of Christianity. Even the staunch atheist cannot help but feel besotted by the soaring nave of Notre Dame or to stand awestruck looking up at the dome of Florence Cathedral. Yet, upon hearing of viewers swooning as a result of divine piety in front of Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s Ecstacy of St. Teresa (1647-1652), the cynic surely questions: Would they have done so if experiencing the sculpture in a broom closet, or in the quietly contrived setting of the Contemporary art museum? Is it only the grandiose devotional spaces where we encounter these artworks that dictate the impending enormity of our experiences?

Fused through Désiré Feuerle’s radical re-interpretation of both art and display, both concept and context are essential to the viewer’s experience. Hence, the work is not dependent of its setting but rather becomes it. Arguably, it is this transcendence that elevates these pieces to new levels of viewership.