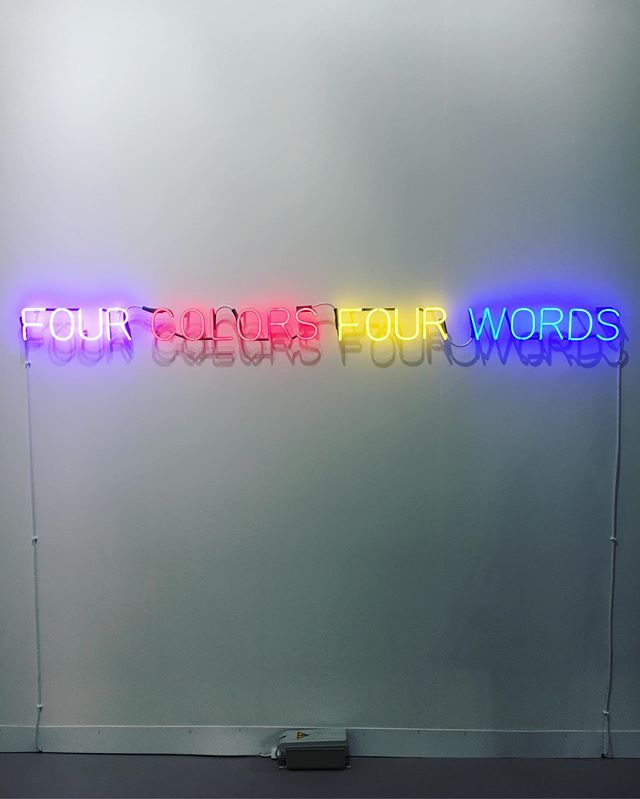

Galerie de Bellefeuille, Montreal

25 August - 04 September 2012

Produced in 2012, David Drebin’s Ultimatum City catapults the viewer into the photographer’s imagined world. As if catching a glimpse of a fleeting moment, the beholder is presented with a portal through which another universe, removed from his/her own, can be experienced. Far from transient, the illustrated scene oozes narrative and intrigue, and at least upon preliminary inspection, there is no reason to doubt its authenticity.

Seemingly vacillating between reification and critique of established gender roles in Western society, the work depicts a woman fulfilling Drebin’s own rendition of the “damsel in distress” prophecy. While there is no male present in the photograph, we sense that he is just beyond the periphery of the image, as our heroine is relegated to a supporting role, indisputably acting in response to his actions. Helpless against the nocturnal panorama of imposing skyscrapers, her existence seems fleeting. The illusory nature of her performance is central, as the concept of performativity permeates the picture. Reality is swallowed by myth; only fantasy remains. Lionized through cinematic genres and popular culture, this proverbial scene has been witnessed before. Thus, a sense of familiarity is triggered within the viewer, as the narrative concurrently rubs shoulders with a recognizable dialect and an alien world.

It is easy to advance a simulacral reading of Drebin’s Ultimatum, analyzing the photograph as referential. Formulated by Jean Baudrillard, the philosophical treatise describes the illusive nature of our constructed reality by the interaction of empty signifiers. Consequently, the image is released from a deeper meaning and exists only superficially as simulacra. It is precisely this strategy of conceptual appropriation from mass media idealism which proliferates, rather than denounces, the male gaze, as the beholder inadvertently morphs into a willing voyeur. Hence, the shiny pixelated surface of the image becomes as vacuous as the female it depicts.

One could posit that the fundamental difference between art and entertainment is that the latter never posed a problem it could not solve. While it is difficult to dismiss Ultimatum on visual grounds, its placement – or rather misplacement – within the commercial art sphere both confounds and confronts. The image may gracefully adhere to a set of purely aesthetic rules, but conceptually it does not permeate the realm of art. Through Drebin’s implicit acceptance of established gender roles, the societal issue appears to be resolved. Or perhaps the problem, masked behind the photographer’s dazzling veil, was never exposed.