Published in Art & Museum Magazine, Spring Issue 2017 (The Inaugural Issue)

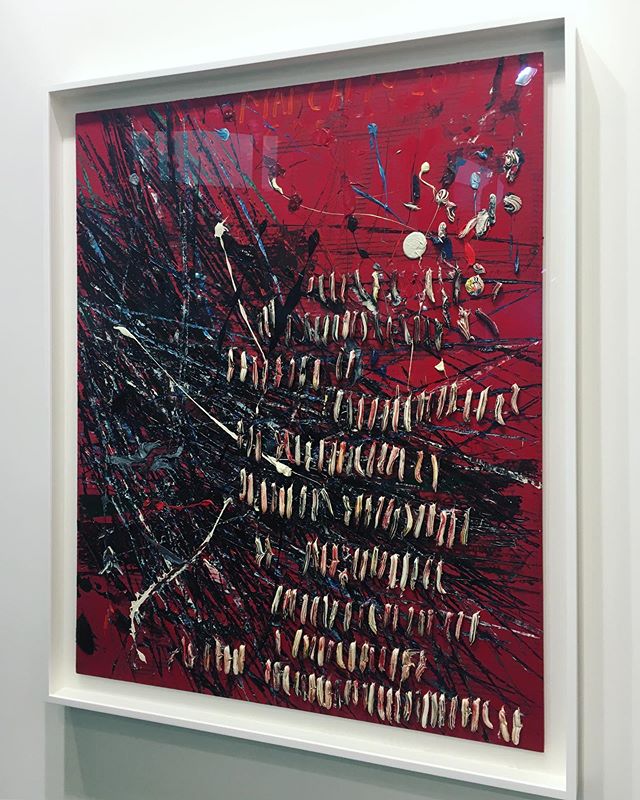

Flanked by two Eileen Gray chairs, Cy Twombly’s 1982 Naxos triptych is displayed. On the adjacent wall, Rudolf Stingel’s aluminium covered Celotex insulation board (Untitled, 2002) is juxtaposed against a Jean-Michel Frank minimalist shagreen cabinet. The pieces carry an underlying intellectual rigour that helped redefine 20th-century design, as well as Contemporary art. Engendering a haphazard narrative, the four works coalesce to form a different kind of dialogue, one that is distinct from the museum realm. Moving away from the white cube, these privately owned oeuvres – now housed in an Eaton Square townhouse – are cloistered from the rest of the world. Their chance placement and the consequential visual exchange it creates was not the work of a museum professional but rather of Jacques Grange, the esteemed French interior designer who rose to prominence after decorating Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé’s Paris residence.

While the artworks here are exhibited outside the museological sphere, they are still intrinsically linked to it as their history ensures that they are firmly anchored within the art canon. It is precisely this deeply interlaced relationship between the museum and the private collection that drew me to pursue a career in this field and establish AIB Art Advisory, an independent art advisory firm that offers expert investment advice and curatorial services to private and corporate clients.

Negotiating the unique rapport between the public and private sphere, the curator vacillates between these two worlds. Acting as a gatekeeper of sorts, he/she is charged with creating and managing ties between the institution and the individual. Needless to say, there is a claustrophobically tight circularity between these two facets of the art world; hence, the profession relies heavily on one’s ability to dip in and out of both pools. Arguably this could trigger a discord when it comes to curating the private collection with the public trust.

Today, private art collections are increasingly trying to permeate the educational realm, a realm previously dominated by museums and galleries. For instance, French Moroccan private collectors, Eli Michel and Karen Ruimy, established The Marrakech Museum of Photography and Visual Arts in 2013 to house and display their extensive collection of fine art photography. Open to the general public, the curatorial program sought to further our knowledge and understanding of post-war photography. Furthermore, foundations, such as The Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, are now providing new collectors with opportunities to exhibit their work more publicly. Similarly, Beatrix Ruf, Director of the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, founded ‘Pool’, an initiative to curate exhibitions at Luma Westbau in the Löwenbräu Art Complex with artworks owned by Maja Hoffmann and Michael Ringier. In Ruf’s own words: “‘Pool’ does not interpret private collections as merely the representation of individual preferences, but rather as a contemporary document.”

This trend is echoed in the number of startups that are cropping up promising to connect collectors with institutions worldwide. Namely, Vastari raised a significant round of funding while tooting the tag line: “the exhibition connection”. Bernadine Brocker, Vastari Group’s CEO says: “The future of art and technology is a fully integrated experience where collectors, museums and experts can connect, curate, tour their shows and define best practices within international relationships.”

Deviating from the conventional curatorial structure, private art collections are remolding the public’s relationship with art. While this undoubtedly broadens our exposure to great oeuvres and deepens our knowledge of the art canon, curators need to be mindful of their responsibility when bridging the gap between public and private establishments, and managing diverging interests. This conflict, intrinsic to the art world, can be perceived when private collectors and foundations choose to employ curatorial labor. Thus, custodians of public museums often simultaneously curate private collections. While their shadow role could be justified as donor cultivation, it still raises some ethical concerns. The Trussardi Foundation, The Kadist Art Foundation, as well as the wealth management firm Northern Trust, all count amongst their advisors esteemed museum directors and chief curators, namely Massimiliano Gioni (Associate Director and Director of Exhibitions at the New Museum), Jens Hoffman (Director of Special Exhibitions and Public Programs at the Jewish Museum New York), Larry Rinder (Director of Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive), Hou Hanru (Artistic Director of the MAXXI in Rome) and Michael Darling (Chief Curator at The Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago).

In an article written for ArtSlant, art writer Ryan Wong posits: “Within the art world, museums still set the standard for critical debate, the resuscitation and reexamination of artistic legacies, and scholarly research within the art world: their exhibitions are the most consistently reviewed, they command the largest spaces, and they attract the most visitors. But they no longer have a monopoly on that work.” The borders surrounding these two once distinct spheres – the institution and the private art collection – are beginning to erode. Hence, collecting has transitioned away from a manifestation of personal taste into a new realm; it is now a curatorial project. This relatively new phenomenon will shape our understanding of history and ultimately redefine the art canon.